The sarong is a popular traditional lower garment in East Asian communities and has several distinctions based on the individual history or practices of distinct tribes. In the northeastern region of India alone, the ethnic diversity of people living along the Eastern Himalaya have stylistic differences in weaving patterns, colours and symbols arising from native traditions and belief systems that seek to assert identity. For the Meitei community which forms the majority ethnic population in the valley of Manipur, the phanek (sarong) is considered sacred and is symbolic of feminine identity; conventional beliefs discourage men from touching it. Even the manner of wearing the phanek is significant; traditionally, adolescent women wear the phanek around the waist (khoidom setpa) and married women wear it around the chest (phidon chingkhatpa).

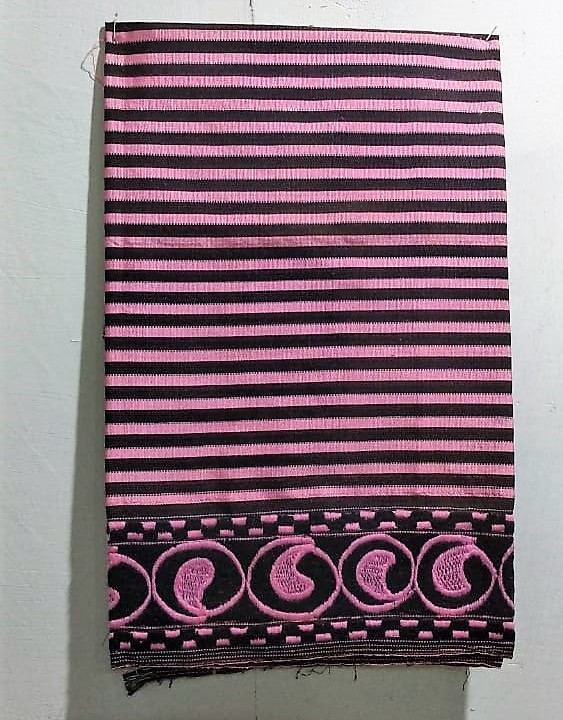

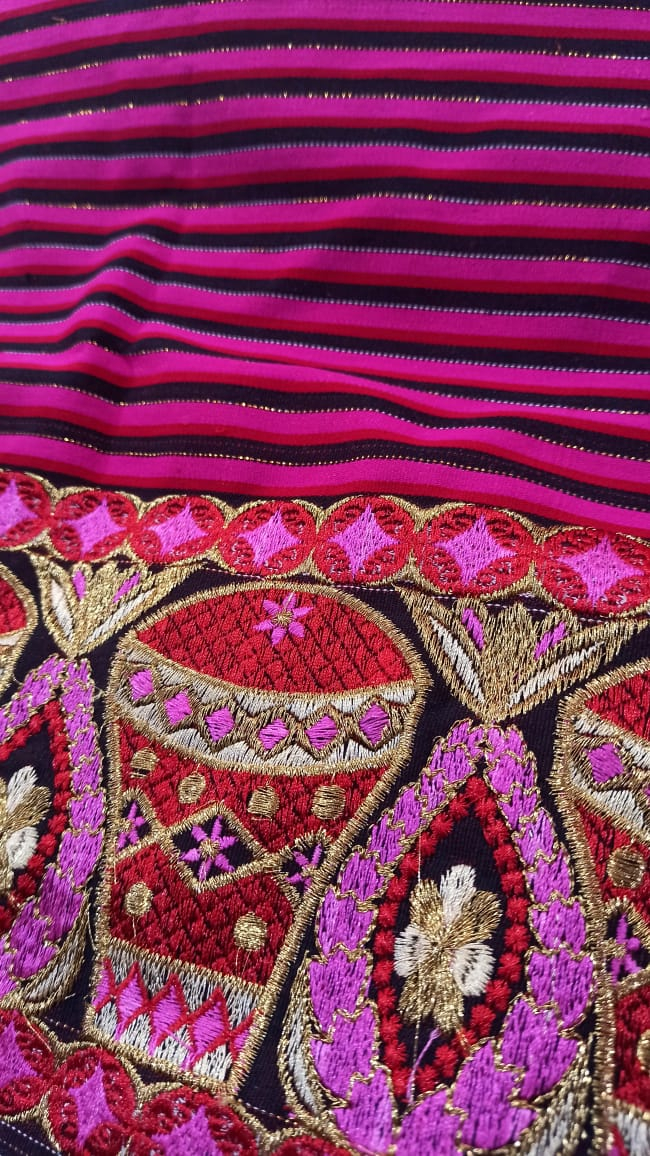

There are broadly two kinds of phaneks in the Meitei community. The pumngou phanek is worn for daily use and is generally devoid of printed patterns, though some have the yairongphee (cloth with teeth border), popularly known as moirangphee (Moirang cloth) pattern lining the top and bottom, and resembling the teeth of Lord Pakhangba (the serpent god). This design is popularly known as the Taj Mahal hakpee (pattern). Pumngou phanek is usually white, light pink or eggshell cream and is worn for religious events. On the other hand, phanek mayek naibi (literally, patterned phanek) is a striped phanek with thick embroidered border along the top and bottom sides. It is worn primarily on auspicious occasions and forms a part of the complete traditional ensemble for Meitei women along with an innaphee (a thin, delicate wraparound for the upper body with intricate embroidery) and a blouse. This phanek is composed of two halves, each with a bold embroidered border on one side; the sides that do not have a border are stitched together horizontally. The phanek is then sewn vertically halfway to allow free size adjustments, and extra weft braiding in white and punggri (deep red) run along this vertical edge. During religious performances, which might include donning the role of religious characters, the participants wear a phanek mayek naibi paired with a khwangyet (waistcloth) and special headgears like in the Thoibi dance, which is an integral part of the Moirang Lai Haraoba festival.

The kanap and pumthit phaneks are two other kinds of phaneks but their use is rare. The kanap is a laiphi (cloth for god) and is part of the queen’s coronation attire. The pumthit phanek was reserved only for the eldest princess (tamphasana) and was rarely available even when the tradition of wearing it was alive.[1]

Vital Motifs

The Cheitharol Kumbaba is a chronicle of the kings of Manipur, starting from 33 CE until Meidingu (king) Bodhchandra (1955 CE), maintained by royal scribes and recorded in archaic Meitei script. It notes that the khoi mayek (hook pattern) in phanek mayek naibi was introduced during the reign of Yanglou Keiphaba (AD 969–984); his wife, Lairenjam Chanu Mubisu, was a famed weaver and is credited for creating the khoi pattern that resembles a hook as well as a bee. Prior to this, a striped phanek without embroidered borders was a common feature of diverse communities in Manipur; hence, it is often concluded that the emergence of phanek mayek naibi was a distinguishing factor for Meitei women to assert their identity and differentiate themselves from other communities in Manipur. The striped phanek with a plain border is known as tungkap and its use is now limited to miniature designs reserved for religious worship or to wrap a female baby on Shasti puja, the sixth day after her birth.

While contemporary society has seen a growth in terms of new motifs and colour schemes, the earliest motifs were limited to two basic designs, khoijao and hija patterns, carrying influences from folk tales and regional specificities. The khoijao (big hook) motif (Fig. 1) is a series of circular patterns which encompasses a large hook-shaped symbol. The outward corner of each hook faces upward and downward alternately, and the border is flanked by two narrow strips of embroidery on either side. The motif is first carved on a wooden block, printed on the cloth and then silk threads are embroidered over the print.[2] It is significant to note that this motif is not limited to phaneks. It can be recurrently seen on the borders of wanphak phurit (a type of jacket), traditionally worn by female members of the royal family; awarded to women specialising in certain vocations; and embroidered on saikakpa phurit (sleeveless shirt), given as rewards to courageous warriors.

Hija mayek (pattern of the Hijam family), on the other hand, was introduced by Kondraba, the chief carpenter to the royal family, who belonged to the Hijam family of the Luwang clan, who were skilled at making boats.[3] Kondraba conceived the hija mayek pattern while making a boat. Thereafter, the royal weavers created an artistic representation that mimics the cross section of timber. (Fig. 2) The ‘W’ on the lower line echoes the Meitei alphabet sam, arranged facing upwards and downwards alternately. The border is flanked at both sides with ornate embroidery. The pattern in the top strip resembles a flowering creeper with leaves on the side and is known as khongnang. The bottom margin is decorated with the tenawa (parrot) figure, again placed alternately up and down and enclosing a yensil (wood sorrel) leaf motif.[4]

Khoi akoibi (approximate translation: rounded hook design) evolves from the earlier khoijao design. (Fig. 3) It is a relatively newer addition and perhaps the most popular motif as well. Each circular pattern is interjected by the curve of a strained tenga (bow). It is followed by two crescents inspired by the moon and is known as tha-machet (tha is the moon and machet means a small piece). The circle at the centre mimics a pot, the symbol for divine mother who nourishes all living beings. The big circular pattern circumscribes a diamond-shaped pattern with two hooks radiating outwards on each side. The circle at the core represents a pitcher surrounded by distinct oval figures. The bigger ovals are cucumber seeds and the smaller ovals are apple seeds.[5] The khoi applique is also used in potloi (a bridal wear for the lower body).

Weaving and Textiles

According to Sanamahism, Goddess Leimarel (mother goddess of all creations) is credited with introducing weaving as a significant aspect of the creation of the universe, and Goddess Panthoibi (goddess of power, war, courage, etc.) is said to have taught humans the art of weaving.[6] Hence, the skill of weaving was considered a crucial asset in Manipur. Women were mandatorily taught weaving, through which they supported income generation for the family.

Historically, the weaving industry in Manipur has been dominated by women. Each house used to have its own loom to weave clothes and these household looms are still prevalent in rural areas. In India, as a whole, approximately 72 per cent of all handlooms are run by women.[7] Consequently, the industry has been pivotal in terms of women’s empowerment by enabling financial freedom and economic agency. The khwang (loin loom), pangiyong (throw shuttle) and phisha kon yonkham (fly shuttle loom) are most widely used in Manipur. (Figs 4 and 5) While the practice of weaving is still more concentrated in household production rather than large-scale industrial production, certain customs have been replaced by modern conventions. Before the introduction of manufactured dyes, blue and black colours were extracted from the kum tree (Strobilanthus flaccidifolus) and saffron from kusum flowers (Schleichera oleosa). These plants were easily grown at home and were abundantly available in the hills of Manipur.

Cotton and silk are used for weaving these phaneks, and even the cotton yarn and silk yarn used to make these respective fabrics are made at home. Naoroibam Indramani, acclaimed writer of many books on Manipur’s history and culture, notes that Loi (subdued or tributary) villages, conquered by the Meitei king and forced to pay taxes, paid silk as tribute to him.[8] Among the residents of the village, the Langloi community exclusively reared silkworms—other Loi communities were not allowed to contribute in this production—and the weaver community in Kabo valley were authorised to weave this silk. Cotton, too, was another crucial tribute paid to the Meitei king by semi-autonomous communities who lived on the hilly terrain. It is easy to see that weaving and textiles were an integral part of Manipur’s history and growth. A loom used to be a part of the wedding trousseau, signifying hope for self-reliance and productivity in marital life. Women’s participation in the economic market, therefore, ensured a reliable livelihood and emancipation from the idea of a conventional male breadwinner.

Identity and Culture

Earlier, the seven Meitei clans distributed seven distinct colours of the phanek mayek naibi among themselves to mark their separate identities; the Ningthouja/Mangang clan had thambalmachu (lotus pink), Angom clan had Langhou (black and white equal stripes), Luwang had higok (blue), Khuman had kumjinbi (dominantly black with narrower white stripes), Moirang had hangamapal (mustard yellow), Chenglei/Leishangthem had loirang (white and light pink), and Khaba Nganba had chingonglei (acacia yellow).[9] While the restrictions pertaining to the methods of production and usage of these phaneks are no longer as rigorous as they were in the past, they continue to occupy a central place in the social and cultural landscape of the region. Different leikais (localities) enjoy different specialisations, and, of these, the Singjamei Maibam leikai is perhaps the most well-known for its loin-loom weaving.

For conservationists of the unique applique work in these motifs, there is a growing anxiety that globalisation and mass production have eroded the quality and craftsmanship of indigenous weaving practices. There is also the additional risk that these motifs that are embedded with traditional folklore and culture will be appropriated by commercial interests who will profit off its emotive and cultural value without sharing the benefits with the community to which they belong.

If culture and identity are dynamic concepts, evolving over time according to context, the changes need to be complemented with conservation strategies. The innaphee, for instance, was earlier made of uriphi (barks of creeping plants), but the innaphee we know today is made of fine cotton or silk and decorated with simplified motifs that have evolved from earlier designs. It enjoyed royal patronage and the weaving industry was encouraged, both for royal customers as well as the masses. It is celebrated as an heirloom, passed down generations, and cherished for its connection to ancestors. These phaneks are no longer held by hierarchical rules of social order, but they continue to strive for a high standard of beauty. (Fig. 6) The primary course of action to conserve these traditional motifs, which are entwined with Meitei identity itself, would be to increase awareness and exposure regarding these prints. Encouraging its skilled craftsmanship and reinforcing its symbolic and cultural value would allow a consolidation of its market value.

(Many thanks to Dr Sobita K. Devi, former director of the Art and Culture Department, Government of Manipur, and founder of The Heritage Foundation for Mankind, for her valuable insights.)

Notes

[1] Devi, Traditional Dress of the Meiteis, 50.

[2] Barbina, ‘Textiles of the Meiteis.’

[3] Indramani, ‘Manipuri Textile,’ 45–77.

[4] Devi, Traditional Dress of the Meiteis, 45.

[5] Ibid.

[6] Ibid., 1.

[7] Ministry of Textiles, Government of India, 4th All India Handloom Census 2019–2020, 33.

[8] Indramani, ‘Manipuri Textile,’ 69.

[9] Devi, Traditional Dress of the Meiteis, 97.

Bibliography

Ministry of Textiles, Government of India, 4th All India Handloom Census 2019–2020. Delhi: Ministry of Textiles, Government of India, 2019.

Indramani, Naoroibam. ‘Manipuri Textile.’ In The Socio-cultural and Historical Accounts of Manipur. Imphal: N.I. Publications, 2015.

Bihari, Nepram, ed. Cheitharol Kumbaba: The Royal Chronicle of Manipur. Guwahati: Spectrum Publications, 2012.

Barbina, Rajkumari. ‘Textiles of the Meiteis: Some Observation on the Fabrics and Designs.’ Heritage: Journal of Multidisciplinary studies in Archaeology 2 (2014): 516–529. Accessed June 10, 2019. http://www.heritageuniversityofkerala.com/JournalPDF/Volume2/516-529.pdf.

Devi, Sobita K. Traditional Dress of the Meiteis. Imphal: Bhubon Publishing House, 1998.